In observance of National Women’s month here in March 2022, I’ld like to share this story.

Mrs. Jack Gardner is one of the seven wonders of Boston. There is nobody like her in any city in this country. She is a millionaire Bohemienne. She is the leader of the smart set, but she often leads where none dare follow… She imitates nobody; everything she does is novel and original.

— A BOSTON REPORTER

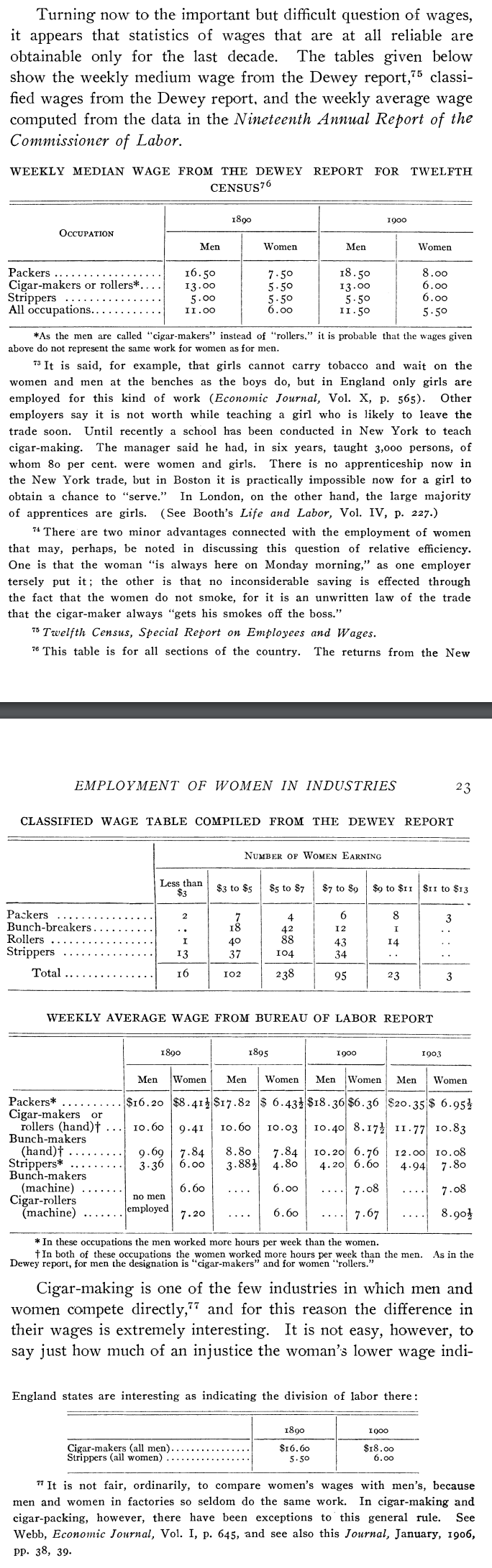

In a January 1907 article titled “Employment of Women in Industries: Cigar-Making: Its History and Present Tendencies” by Edith Abbott, writing from Washington, DC, on pages 1-37 of the Journal of Political Economy, some interesting observations–supported by evidence–are laid out.

The increased employment of women in cigar-making seems to indicate its tendency to develop into a “women’s industry” and furnishes an interesting example of the industrial displacement of men by women. The history of the industry makes it of peculiar interest, because originally the women were displaced by the men, and in these later years they have only come into their own again.

The manufacture of cigars in this country is an industry of nearly a century’s growth, but it has not continuously through-out its history employed a large proportion of women. This is, at first, not easy to understand, for it has always been a trade for which women are seemingly better qualified than men. No part of the making of cigars is heavy work, and skill depends upon manual dexterity–upon delicacy and sensitiveness of touch. A brief description of the three important processes in a cigar factory-“stripping,” “making,” and “packing”–will serve to make this quite clear.

The preliminary process, of “stripping,” which includes “booking,” is the preparation of the leaf for the hands of the cigar-maker. The large mid-rib is stripped out, and, if the tobacco is of the quality for making wrappers, the leaves are also “booked”–smoothed tightly across the knee and rolled into a compact pad ready for the cigar-maker’s table. Even in the stripping-room there are different grades of work, all unskilled and all practically monopolized by women and girls.

The stripping of the “filler” leaf for the inner “bunch” of the cigar is usually piece-work, but the stripping of the wrapper and binder is likely to be time-work, to avoid such haste as might tear the more expensive leaf. If a woman “books” her own wrappers, she gets higher pay than one who merely “strips ;” and one who only “books” gets more than either, for this is much harder work and keeps the whole body in motion. The scale of wages in a large union factory in Boston furnishes a measure of the supposed differences in these occupations: binder-stripper, $6 a week; wrapper-stripper who “books,” $7 a week; filler-stripper, $6 to $Io a week. The lack of skill in any of this work is indicated by the fact that in places where the union requires a three years’ apprenticeship for cigar-making two weeks is the rule for stripping, and competent forewomen say that “a bright girl can learn in a day.” In England the situation in this occupation is rather different. “The work is well adapted for female hands, and in provincial factories they are largely employed in this department. In London, on the contrary, there seem to be not more than thirty women engaged as strippers.” (Booth, Life and Labor of the People, Vol. IV, p. 224.)

Division of labor has been slow in making its way into cigar factories. The best cigar is, still made by a single workman, and the whole process demands a high degree of skill. Slightly inferior cigars, however, can be made with “molds” by less skilled workmen.

Wage disparity between women and men is a long-standing issue, as shown in these pages from Abbott’s article.

men and women in factories so seldom do the same work. In cigar-making and cigar-packing, however, there have been exceptions to this general rule